Authors: Karen Hargrave, Sarian Jarosz (original article here)

On late Sunday evening an exit poll from Poland’s parliamentary elections delivered a surprising and deal-breaking result, later confirmed as votes were counted: the now-ruling Law and Justice (PiS) is set to be unable to form a government for a third term, with Donald Tusk’s opposing Civic Coalition poised to take power in coalition with other parties.

Billed as the most important election since the fall of Communism and an existential battle for the country’s soul, Poles turned out to vote in record numbers. The election campaign was characterised by fierce personal enmity between PiS chairman Jarosław Kaczyński and Donald Tusk, and rhetoric described by the OSCE as ‘intolerant, xenophobic and misogynistic’.

Migration and security once again became a key battleground, as a proxy for Poland’s place in Europe, relationships with the EU, Germany, Belarus, Russia and the rest of the world. Building on previous and ongoing ODI research, we look back at narratives that emerged during the election campaign and ask: what do they tell us – and what next for policy surrounding migration and refugees in Poland?

Rhetoric on asylum and migration: something old, something new?

In Poland’s 2015 parliamentary elections the PiS swept to power on the back of a campaign that, in the midst of Europe’s so-called ‘refugee crisis’, cast Muslim refugee arrivals as a threat to Poland’s culture, health and security. The campaign evoked negative representations of Muslim immigration to other parts of Europe, with Kaczynski asking, ‘Do you really want the same thing to happen in Poland: that we stop feeling at home in our own country?’

In many ways, this year’s PiS campaign felt like a reprise. Though lacking a crisis on the continent they sought to manufacture one, focusing on the recent EU Migration Pact and putting forward a referendum, held on the same day as the election, on the ‘admission of thousands of illegal immigrants from the Middle East and Africa under the forced relocation mechanism imposed by the European bureaucracy’. In a video posted on social media about the referendum, images were shown of burning cars, street violence and a black man licking a knife.

Like in 2015, the PiS sought to capitalise on Polish suspicion of the EU and ‘Brussels elites’, epitomised by opposition leader and former President of the European Council Donald Tusk. But while in 2015 individual refugees and migrants were cast as the primary villains of Poland’s migration story, the recent PiS campaign reflected a subtly evolved narrative whereby refugees and migrants are depicted as pawns in a greater geopolitical conflict.

This narrative is particularly linked to events on the Poland-Belarus border, where since 2021 refugees and migrants have been arriving from the Middle East and Africa, with well-documented instrumentalisation by the Lukashenko regime in Belarus. Those arriving in Poland have been met with hostility and violent pushbacks, while being cast by the PiS as part of a ‘hybrid attack’ on Poland.

The PiS government has criminalised solidarity, depicting humanitarian activists as colluding with Poland’s enemies. During the election campaign PiS politicians led a backlash against The Green Border, a new film by Polish director Agnieska Holland. The film, depicting the humanitarian crisis on the border, was likened by the PiS’ justice minister to Nazi propaganda.

A rejection of anti-immigration rhetoric?

Not only did the PiS fail to secure a parliamentary majority, but – despite record election turnout – its referendum failed to secure the participation needed for it to be considered valid, amid mass calls for boycotts and legal analyses highlighting its illegitimacy.

Was the result a rejection of the anti-immigration rhetoric that has dominated Polish politics and media since 2015?

Public opinion data on the Poland-Belarus border situation has been mixed. On one hand it suggests overall support for the government’s response. On the other, a majority are opposed to more hardline aspects, such as cutting off access to the border for media and humanitarian organisations.

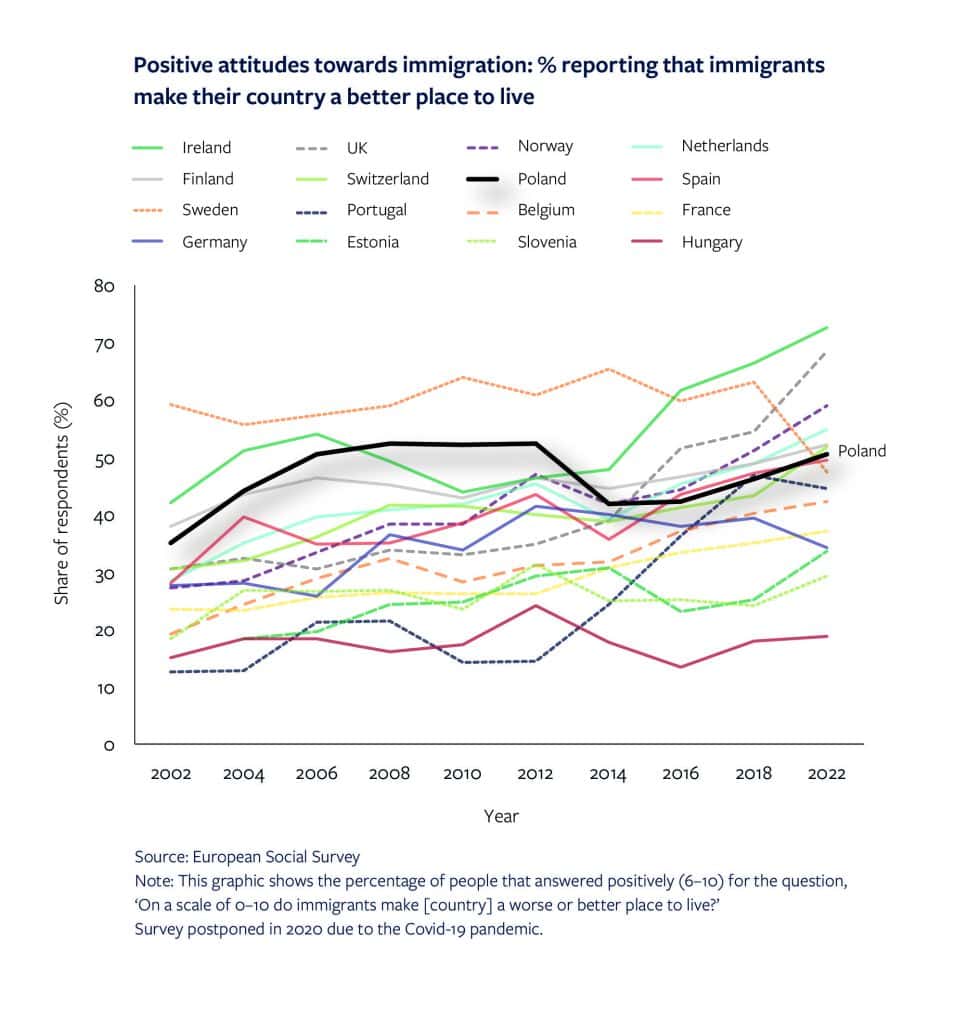

By some metrics Poland ranks as one of the more positive nations in Europe on immigration. According to the European Social Survey, half of Poles feel that immigration makes Poland a better place to live, with attitudes generally more positive over the last two decades in line with broader trends across Europe.

Meanwhile, according to Eurobarometer, in June 2023 – in the wake of the pre-election campaign – just 7% of Poles ranked immigration one of the top two issues facing the country (compared to 17% in 2015), amidst dominant concerns about the cost of living.

But as ever, the story is complicated, not least because the opposition has also sought to make a political issue of migration.

In the weeks ahead of the election, a ‘cash-for-visas’ scandal emerged, involving allegations that EU Schengen visas were issued at Polish consulates in the Middle East and Africa in exchange for bribes. Tusk was accused by other opposition parties of launching a ‘bidding war’ on anti–immigrant rhetoric, as he linked the scandal to wider increases in immigration under the PiS. A Civic Platform advert decried how ‘the PiS government invited 250,000 immigrants from Asia and Africa to Poland – more than France and Germany […] They [PiS] scared us [with immigrants] but they themselves let them in.’

Shifting opinion and narratives on Ukraine

Also notable was the fact that – despite approximately one million refugees from Ukraine currently hosted in Poland – neither of the main parties sought to make this a political issue.

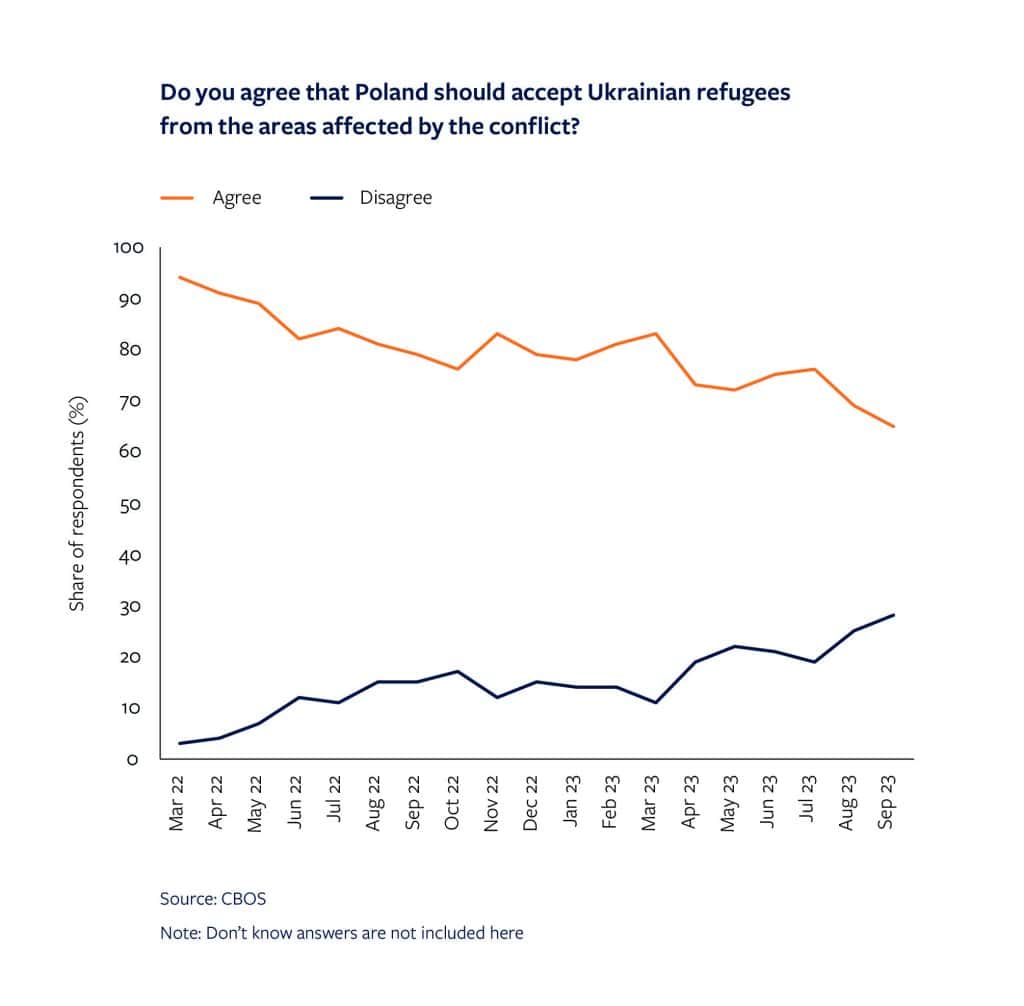

This is despite growing ‘compassion fatigue’ and shifting public sentiment. According to CBOS, a Polish public opinion polling institute, in September support for accepting refugees from Ukraine dropped to its lowest point since March 2022, though with the majority remaining positive. While last March an overwhelming 94% of Poles supported accepting those fleeing the war, amidst a wave of bottom-up support across Polish society, there is today a growing minority – currently over a quarter of Poles – who are opposed to doing so.

Notably, in September the government announced plans to cut social benefits to refugees from Ukraine. This reflected a broader narrative shift from Poland’s government – particularly centred on a dispute over the import of Ukrainian grain – moving from almost boundless solidarity with Ukraine to making clear that Polish interests would always come first. Donald Tusk expressed a similar position on cutting financial support to refugees, stating that ‘there is nothing anti-Ukrainian about it. But as long as someone is not a Polish citizen, these rights must be different’.

Looking forwards

As a new government is formed it will face challenges from a presidential veto from PiS-aligned Andrzej Duda, as well as an uphill struggle of uniting both a polarised nation and an unwieldy coalition of parties, which have united to break nearly a decade of right-wing rule.

Many questions remain for the future of policies on migration and refugees, including how a government led by Tusk would reconcile his attacks on the PiS’ immigration record with the undeniable reality that, facing labour shortages and an ageing population, Poland’s economy needs foreign workers.

Policies towards refugees from Ukraine are likely to become increasingly salient, in the face of shifting public sentiment and anti-Ukrainian propaganda. Another issue is how Poland – and the EU – will address the clear double standard in refugee reception, where hospitality towards Ukrainian refugees contrasts with securitisation on the Poland-Belarus border.

One thing though is evident: in the current context, hostile anti-refugee and anti-EU rhetoric is not the outright election-winner it was in 2015. While optimism feels premature, for the first time in almost a decade there is an opportunity for a new government to chart a different course: designing migration policies fit for the turbulent years to come, balancing a divided nation’s expectations of security, hospitality and economic prosperity.

Authors: Karen Hargrave, Sarian Jarosz